Persia, Land of Legends

Although the Persian carpet became known in Europe sometime after the Turkish carpet, we will treat it first, thus rendering it deserved homage. In fact, this relatively late popularity is explained by geographical remoteness which throughout the centuries has prevented familiarity with far-off lands because of the high cost and difficulty of overland transport before the arrival of the era of great maritime traffic.

However, let us remember that the most ancient carpets whose existence are discussing originally came from Persia. These are knotted, with hunting scenes, like the Pazyryk carpet, which has come down to us, or the famous carpet of Chosroes, described in the chronicles and which, although woven according to all probability, could be considered the forerunner of the garden-carpets which figure among the most typical of Persian carpets.

The artists who were destined to be the most original in the art of carpet making were born in Persia, land of legends. Their fantastic designs, the cleverly intermixed colors, the incomparable feeling for the arabesque, are all the expression of a people whose decorative instinct burst forth involuntarily. Profoundly different from the Turk, both ethnographically and philosophy cally, the Persian from the beginning was an afflicted, subtle, lucid person. To free himself from his nostalgia, he needed fairytale gardens, horses and falcons for tumultuous and exciting hunts, and shady golden palaces, which inspired his dreams and served as precious tokens to the wife he respected and loved. In this respect, his attitude was quite different from that of the Turk who maintained a medieval attitude. On numerous occasions, the Thousand and One Nights, the enchanting poems of Saadi and Hafiz, the poets of Shiraz (which have an exalted place in Persian culture) allude to the splendor of the carpets which adorn the palaces of the women. We read in the poem of Taj-Al-Mulk:

"How can one resist the voluptuous appeal of the silken carpets, embroidered with gold and silver which decorate the home of Dunya, the fairest of the fair?" The 16th and 17th centuries are the most illustrious periods of Persian art. The miniatures, ceramics, metalwork, and embroideries are sufficient evidence of this. The writings of the important travelers remain also an abundant source of anecdotes. Their sincerity is a refreshing influence and important enough to be a powerful factor in the authentification of theoretical ideas. Thomas Herbert

(1627) tells how Shah Abbas the Great had ordered the manufacture of a carpet

"whose richness would mirror his magnificence." Another historian, Tavernier, stressed that the king held precious carpets in such esteem that he had two servants accompany him always "whose task it was to remove his shoes each time he entered the rooms covered with carpets of gold and silk, and to replace them as he left." Shortly after the death of Shah Abbas, Adam Olearius, the librarian of the Duke of Schleswig-Holstein, after returning from an expedition to the Orient accompanying the latter, told the story of his voyage (1639). Throughout, he painted a picture of a happy and prosperous Persia. He visited Ardabil and Kashan, which he described as an active center of carpet making. He speaks of the clay houses along the narrow alleys where the multi-colored wools were dried out, of the Muscovites whose presence enliven the market and who stored their merchandise in the lower town and in particular, of the many carpets of the Circassians and Jews who brought the finest examples from Tabaristan. Arrived at Khorassan, he goes into ecstasies over the quality of the carpets of Herat and mentions that one meets many Hindus who go there to conduct trade. We will have the opportunity later to discuss the exchanges between India and Persia and their complexity when it comes to judging the Indo-Persian rug, so-called for want of other information.

In the 17th century, wars and internal conflicts slowed down production in Persia. One still comes across beautiful examples, but little by little foreign influences notably European - become more evident, and carpets made to specified orders more numerous. In the 19th century, particularly in the first half, an air of romanticism wafts over a major part of the output, giving rise to pieces often of extreme delicacy and great refinement of hue, while initiating a movement of decadence compared with the traditional production of the great period. This said, we are faced with the question of the age of a carpet, to which we can reply that although it is sometimes presumptuous to wish to locate the place of origin, nevertheless, a certain experience permits us to state approximately its date of manufacture by means of its feel, appearance and the degree of wear on the one hand, and on the other, by means of familiar historical facts.

WHAT DOES A PERSIAN CARPET LOOK LIKE?

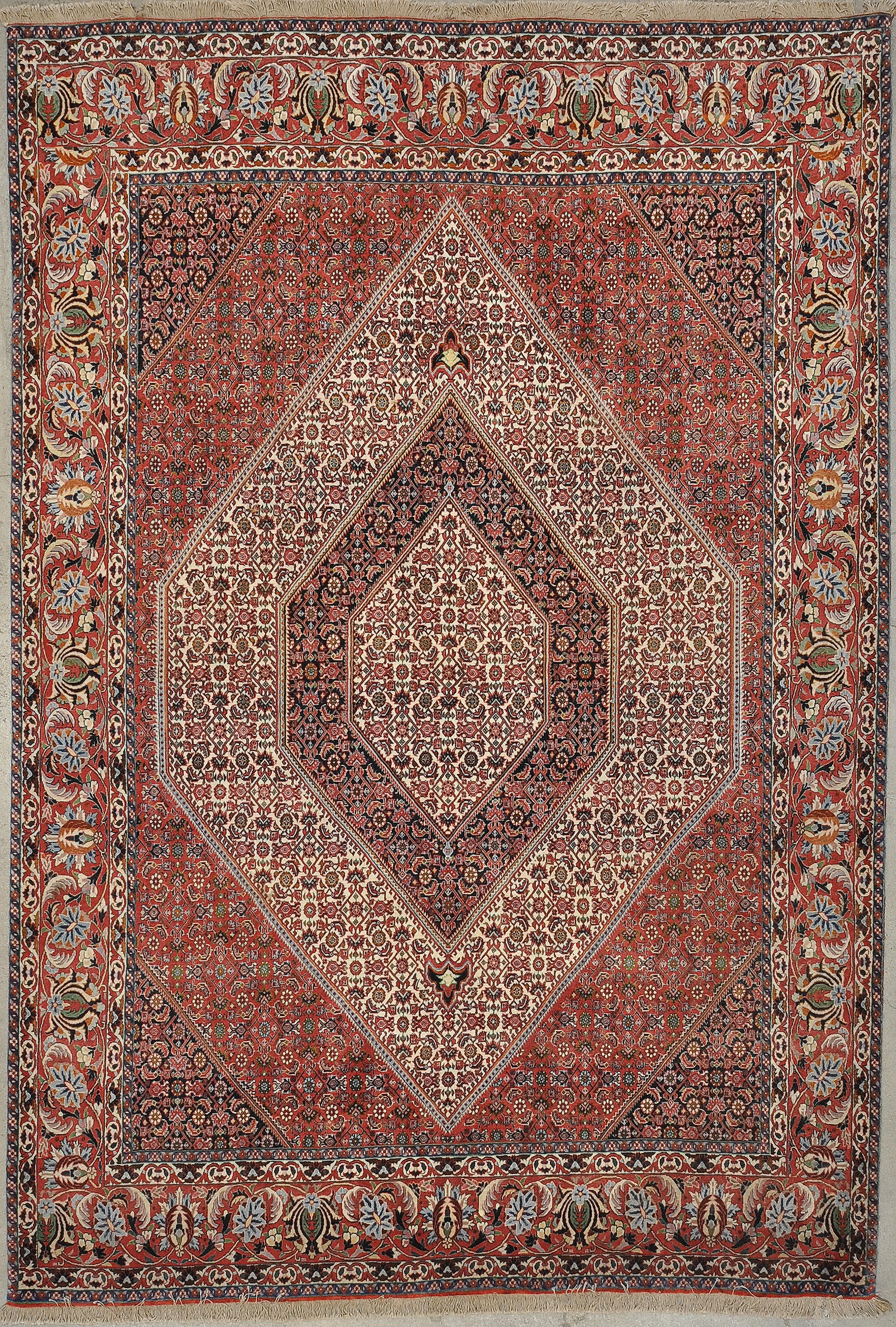

Leaving aside the fact that Persian art is strictly allied to a highly developed poetic sense, as well as a taste for nature free from religious dictates, we can say that we recognize a Persian carpet first of all by the great freedom of form, its con structure, and decorative imagination. From this spring the innumerable variations of floral motifs, shields of foliage, palmettes, skillful arabesques, garlands, fantastic or legendary animals, and figures of all kinds, treated generally in a figurative manner and with great difficulty contained within the architectural The color scheme is in a low harmonious key enriched with pure tones; for limits of the scheme.

instance, the shaded pinks, and greens are heightened by an ultramarine or the deep reds by orange and beige, and so on. And when examining silk carpets, we must always remember that silk retains the dye less than wool and therefore will have become faded.

One can operate a clear and efficient system of classification for the Persian carpet by means of its decorative structure. Furthermore, such a classification is adopted by many museums and exhibition catalogs.